My first encounter with Sempé was the first book of “Le Petit Nicolas.” It had been given to my brother as a gift, but I read it myself. It was the 1980 edition published by Alfaguara. On the cover, a red smudge distinguished Nicolas as he walked neatly in line out of school. The funniest thing was that the line ended up breaking into a stampede. I could spend hours looking at that cover because I was fascinated by it.

I have never read anything so funny again. To this day, I still think that Sempé’s illustrations from the 1960s have never been surpassed, not even by himself.

That year I was in fourth grade and the teacher asked us to bring a book to read in class. After thinking about it a lot, I decided to bring “Le petit Nicolas.”

When it was my turn, I went up to the blackboard and read the first episode. I felt that my classmates weren’t the least bit interested, but Miss Milagros was captivated. First, she asked me about the strange names of the characters (Agnan, Alcestes, etc.) and then asked me to lend her the book. For me, it was confirmation that The Little Nicholas wasn’t just a book for children. It’s funny that now, in 2022, with the release of the animated film of Le Petit Nicolas, they mention that Goscinny carefully chose those funny names, which are also strange in France.

The animated film is faithful to Sempé’s original style, after those awful previous live-action and CG adaptations, although I still think it’s practically impossible to reproduce those pen-and-ink drawings with the same level of evocativeness that you see on a printed sheet of paper.

I think it’s a bit like silent movies. You can’t recreate the same feeling even if you try to imitate it. It’s part of another era and another sentiment.

About the film

The film is an excellent fusion of Sempé’s style in his colorful New York illustrations with black-and-white newspaper cartoons. Although the adaptation is a purely digital work, it manages to maintain an organic and faithful look.

The script adds a “biopic” element that touches on the lives of Sempé and Goscinny, and this part features slightly more realistic drawings that are closer to the New York illustrations. The biographical story is concise and simple, suitable for a non-specialist audience, but it is interesting nonetheless.

On a technical and artistic level, the film’s work is difficult to improve upon. Only the animation, which is limited, falls a little short, possibly due to the budget, although this does not make it any less imaginative. It is obviously digital, which detracts from the charm of Sempé’s real pen strokes, one of his most personal characteristics.

Small variations have been introduced into the stories to adapt them to the format, but in general they are identical. Only a few have been adapted, leaving a lot of hilarious stories on the cutting room floor. The adaptation is faithful and maintains the original essence of Goscinny.

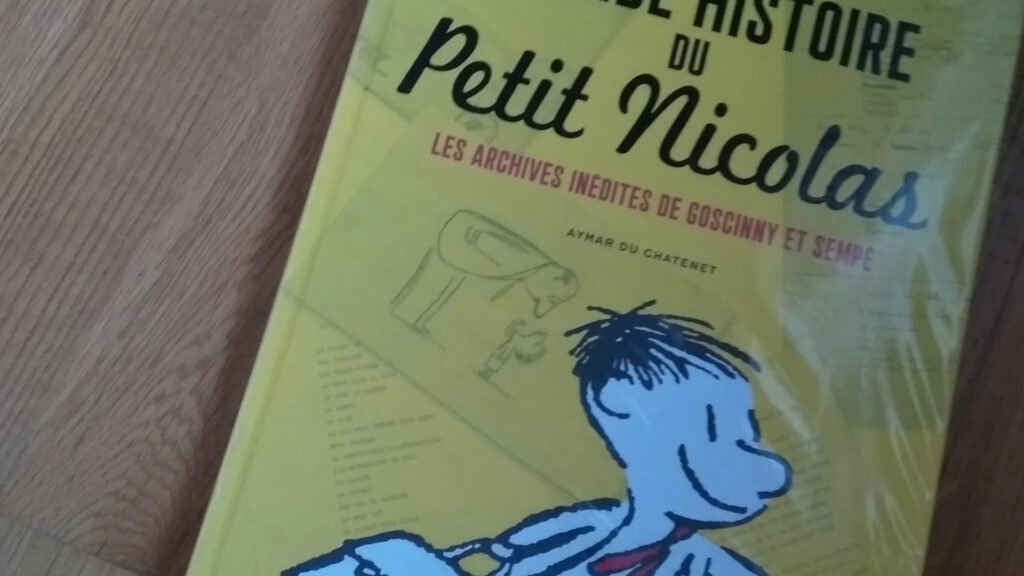

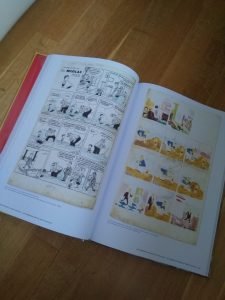

In France, there is an official website for Le Petit Nicolas. It is this one here. To mark the release of the film, they have published a giant book that takes a historical look at the different periods in the character’s life and the lives of the authors. As far as I know, it has not been translated into Spanish, but it can be found in specialist bookshops such as Librería Pasajes in Madrid. Spectacular design and top-quality material.

Sempé’s style

I always found it difficult to explain Sempé’s genius. For me, his drawings have always been the best by far, closely followed only by the equally brilliant Jules Feiffer. What was Sempé’s secret?

Sempé relied on a seemingly very simple style, but like many other cartoonists, he had a mastery of perspective that I didn’t realize until many years later when he began publishing in the New Yorker. Behind seemingly careless inking lies a very solid foundation. His color, too, was on a par with that of an Impressionist painter.

I believe that Sempé’s work was based above all on high-quality composition in which he always alternated contrast.

The contrast between crowded spaces and empty spaces, the contrast between fine lines and thick strokes, the contrast between white and black spots, between large and small, between children and adults, bosses and employees, husbands and wives, the oppressor and the oppressed.

But above all, what set Sempé apart was that “feeling.” Feeling and thought, because his drawings are not seen, they are ‘thought’ and “felt.”

For me, the news of Sempé’s death makes me feel that my entire childhood has gone with him.

Thank you, Sempé. Au revoir, maestro ❤️.